The Six Continents

1878

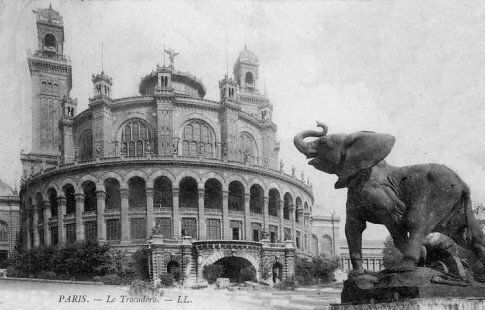

Six heroic cast bronze figures of women, each representing one of the six continents, were commissioned by the City of Paris for the Paris Exposition-Universelle (World Fair) of 1878.

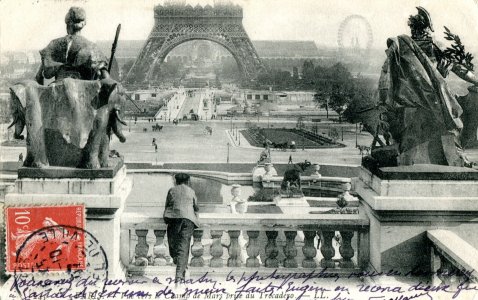

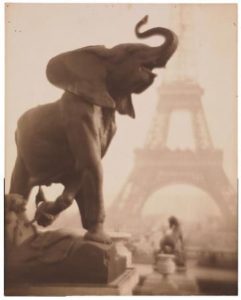

The Continents were displayed on pedestals, three to a side, on terraces flanking the main entrance to the Palais du Trocadéro, where they presided for decades.

1889

From left to right, the Continents are Europe, Asia, Africa and North America (visible in the photo), with South America behind Europe on the far left, and Australia behind North America on the far right.

Note: The sculpture above the entrance was created for the Exposition-Universelle of 1889, which celebrated the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution. Also created for the 1889 Exposition: the Eiffel Tower, across the Seine from the Palais du Trocadéro.

1937

The Palais du Trocadéro was torn down and replaced by the Palais de Chaillot for the Exposition Internationale des arts et techniques of 1937.

1963-1986

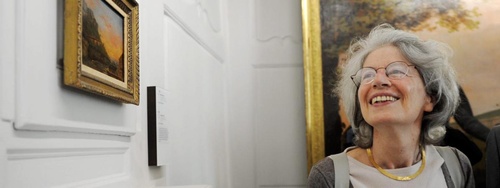

Since 1963 The Six Continents had been consigned to a public dump in Nantes. Anne Pingeot, a respected authority on 19th century sculpture and, at the time, Curator of Sculpture for the Musée d’Orsay, was instrumental in their rescue.

Pingeot located the figures, and arranged an exchange with the City of Nantes, trading a painting by Sisley (now at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes) for The Six Continents.

Where were the Continents between the demolition of the Palais du Trocadéro in 1937 and the move to Nantes in 1963?

We might not know where they were, but the Musée d’Orsay website offers clues to the reason for their disappearance, and their later consignment to a Nantes public dump:

The 19th century was a remarkably prolific period for sculpture: the triumphant middle-class and the political powers eagerly appropriated this art form, the former to decorate its homes and proclaim its social status and the latter to inscribe the ideals and beliefs of the period in stone and bronze. There was huge demand for sculpture which, because of its cost, depended almost entirely on commissions. But from 1945, the art world turned away from the works produced in this period, regarded as too official, and many works vanished into the store rooms for a season in purgatory that lasted for several decades. Only a few major “modern” figures, such as Rodin, escaped from the general disenchantment.

In the 1970s, the idea of converting the Orsay railway station into a museum gave sculpture from the second half of the 19th century a new lease on life. The new museum offered an ideal space for displaying sculpture: the great central nave lit by the changing daylight streaming through the glass roof. The public was able to rediscover the wealth and diversity of sculpture from this period. When it opened in December 1986, the Musée d’Orsay had assembled some 1,200 sculptures… “From Excess to Oblivion“, History of the Collections, Musée d’Orsay.

Where ever they were, The Continents are back in town.

Back in Town: Europa & the Girls

Palais du Trocadéro

The Continent of Europe

The Continent of Asia

The Continent of Africa

The Continent of North America

The Continent of South America

The Continent of Oceania, or Australia

Note: The building that houses the Musée d’Orsay was originally the magnificent Gare d’ Orsay, built for the Paris Exposition-Universelle of 1900. However, its utility as a railway station diminished in 1939 when it was unable to accommodate the new longer trains that came with railroad electrification, limiting the station to suburban service.

Excerpt, “From Museum to Station“, History of the Museum, Musée d’Orsay: The Gare d’Orsay then successively served different purposes : it was used as a mailing centre for sending packages to prisoners of war during the Second World War, then those same prisoners were welcomed there on their returning home after the Liberation. It was then used as a set for several films, such as Kafka’s The Trial adapted by Orson Welles, and as a haven for the Renaud-Barrault Theatre Company and for auctioneers, while the Hôtel Drouot was being rebuilt.

The hotel closed its doors on January 1st, 1973, not without having played a historic role: the General de Gaulle held the press conference announcing his return to power in its ballroom (the Salle des Fêtes).

In 1975, the Direction des Musées de France already considered installing a new museum in the train station, in which all of the arts from the second half of the 19th century would be represented. The station, threatened with destruction and replacement by a large modern hotel complex, benefitted instead from the revival of interest in nineteenth-century architecture…

The building was classified a Historical Monument in 1978 and a civil commission was created to oversee the construction and organisation of the museum. The President of the Republic, François Mitterrand, inaugurated the new museum on December 1st, 1986, and it opened to the public on December 9th.

Carol Goodwin Blick (2017)

Matt Leach and Charles Marchant Stevenson: Paris

Stevenson/Leach Studios

Charles Marchant Stevenson: Artwork

Charles Marchant Stevenson

About Charles Marchant Stevenson

Mendocino Heritage Artists

Homepage