The Madwoman of Chaillot: Written in French by Jean Giraudoux. English Adaptation by Maurice Valency, now in the public domain (2017).

Subject: rights of the poor

Genre: Comedy

Setting: The fashionable Chaillot quarter of Paris

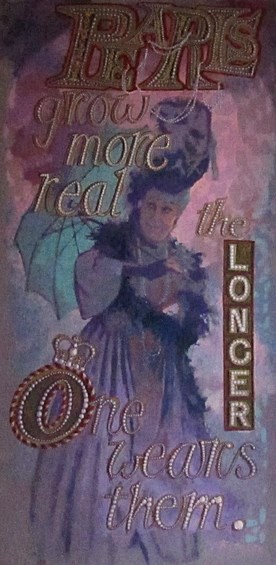

Premiered 19 December 1945, Théâtre de l’Athénée, Paris, produced by Louis Jouvet. First presented in English by Alfred de Liagre, Jr., at the Belasco Theatre, New York, on 27 December 1948. Directed by Alfred de Liagre, Jr. Settings and costumes designed by Christian Berard. Mendocino production of The Madwoman of Chaillot, Nichols Studio, Mendocino Art Center, Mendocino California (1967).

LINKS

Entertainments

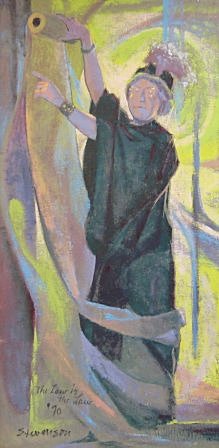

Charles Marchant Stevenson: Portraits

Charles Marchant Stevenson: Artwork

Stevenson in His Own Words

About Charles Marchant Stevenson

Mendocino Heritage Artists

Welcome!

Madwoman of Chaillot: Summary: The play is set in the cafe “chez Francis” in the Place de l’Alma in the Chaillot district of Paris. A group of corrupt corporate executives are meeting. They include the Prospector, the President, the Broker and the Baron, and they are planning to dig up Paris to get at the oil which they believe lies beneath its streets. Their nefarious plans come to the attention of Countess Aurelia, the benignly eccentric madwoman of the title. She is an aging idealist who sees the world as happy and beautiful. But, advised by her associate, the Ragpicker, who is a bit more worldly than the Countess, she soon comes to realize that the world might well be ruined by these evil men—men who seek only wealth and power. These people have taken over Paris. “They run everything, they corrupt everything,” says the Ragpicker. Already things have gotten so bad that the pigeons do not bother to fly any more. One of the businessmen says in all seriousness, “What would you rather have in your backyard: an almond tree or an oil well?”

Aurelia resolves to fight back and rescue humanity from the scheming and corrupt developers. She enlists the help of her fellow outcasts: the Street Singer, The Ragpicker, The Sewer Man, The Flower Girl, The Sergeant, and various other oddballs and dreamers. These include her fellow madwomen: the acidic Constance, the girlish Gabrielle, and the ethereal Josephine. In a tea party every bit as mad as a scene from Alice in Wonderland, they put the “wreckers of the world’s joy” on trial and in the end condemn them to banishment—or perhaps, death. One by one the greedy businessmen are lured by the smell of oil to a bottomless pit from which they will (presumably) never return. Peace, love, and joy return to the world. Even the earthbound pigeons are flying again.

Criticism: Theatre Arts magazine described the play as “one part fantasy, two parts reason.” The New York Drama Critics’ Circle hailed the 1948–50 production as “one of the most interesting and rewarding plays to have been written within the last twenty years…”

Characters:

THE WAITER

THE LITTLE MAN

THE PROSPECTOR

THE PRESIDENT

THE BARON

THERESE

THE STREET SINGER

THE FLOWER GIRL

THE RAGPICKER

PAULETTE

THE DEAF-MUTE

IRMA

THE SHOE-LACE PEDDLER

THE BROKER

THE STREET JUGGLER

DR. JADIN

COUNTESS AURELIA, The Madwoman of Chaillot

THE DOORMAN

THE POLICEMAN

PIERRE

THE PRESIDENTS

THE SERGEANT

THE SEWER-MAN

MME. CONSTANCE, The Madwoman of Passy

MLLE. GABRIELLE, The Madwoman of St. Sulpice

MME. JOSEPHINE, The Madwoman of La Concorde

THE PROSPECTORS

THE PRESS AGENTS

THE LADIES

THE ADOLPHE BERTAUTS

THE MADWOMAN OF CHAILLOT

ACT ONE — The Cafe Terrace of Chez Francis.

Scene : The cafe terrace at ” Chez Francis,” on the Place de l’Alma in Paris. The Alma is in the stately quarter of Paris known as Chaillot, between the Champs Elysees and the Seine, across the river from the Eiffel Tower.

“Chez Francis” has several rows of tables

set out under its awning, and, as it is lunch

time, a good many of them are occupied. At

a table, downstage, a somewhat obvious Blonde

with ravishing legs is sipping a vermouth-

cassis and trying hard to engage the attention

of the Prospector, who sits at an adjacent table

taking little sips of water and rolling them

over his tongue with the air of a connoisseur.

Downstage right, in front of the tables on the

sidewalk, is the usual Paris bench, a stout

and uncomfortable affair provided by the

municipality for the benefit of those who prefer

to sit without drinking. A Policeman lounges

about, keeping the peace without unnecessary

exertion.

TIME : It is a little before noon in the Spring of next year.

AT RISE : The President and the Baron enter with importance, and are ushered to a front table by the Waiter.

THE PRESIDENT. Waiter! Get rid of that man.

WAITER. He is singing La Belle Polonaise.

THE PRESIDENT. I didn’t ask for the program. I asked you to get rid of him. (The Waiter doesn’t budge. The Singer goes by himself) As you were saying, Baron . . . ?

THE BARON. Well, Until I was fifty . . . (The Flower Girl enters through the cafe door, center) my life was relatively uncomplicated. It consisted of selling off one by one the various estates left me by my father. Three years ago, I parted with my last farm. Two years ago, I lost my last mistress. And now — all that is left

THE PRESIDENT. (to the Baron) Baron, sit down. This is a historic occasion. It must be properly celebrated. The waiter is going to bring out my special port.

THE BARON. Splendid.

THE PRESIDENT (offers his cigar case). Cigar? My private brand.

THE BARON. Thank you. You know,

this all gives me the feeling of one of

those enchanted mornings in the Arabian

Nights when thieves foregather in the

market place. Thieves — pashas . . .

(He sniffs the cigar judiciously, and begins

lighting it.)

THE PRESIDENT (chuckles). Tell me

about yourself.

THE BARON. Well, where shall I begin?

(The Street Singer enters. He takes off a

battered black felt with a flourish and begins

singing an ancient mazurka.)

STREET SINGER (sings)

Do you hear. Mademoiselle, Those musicians of hell ?

me IS . . .

THE FLOWER GIRL Violets, sir?

THE PRESIDENT. Run along.

(The Flower Girl moves on.)

THE BARON (staring after her) . So that,

in short, all I have left now is my name.

THE PRESIDENT. Your name is precisely

the name we need on our board of

directors.

THE BARON (with an inclination of his

head). Very flattering.

THE PRESIDENT. You wiU Understand

when I tell you that mine has been a very

different experience. I came up from the

bottom. My mother spent most of her

life bent over a washtub in order to send

me to school. I’m eternally grateful to

her, of course, but I must confess that I

no longer remember her face. It was no

doubt beautiful — but when I try to recall

it, I see only the part she invariably

showed me — her rear.

THE BARON. Very touching.

THE PRESIDENT. When I was thrown

out of school for the fifth and last time,

I decided to find out for myself what

makes the world go round. I ran errands

for an editor, a movie star, a financier . . .

I began to understand a little what life is.

Then, one day, in the subway, I saw a

face . . . My rise in life dates from that

day.

THE BARON. Really?

THE PRESIDENT. One look at that face,

and I knew. One look at mine, and he

knew. And so I made my first thousand —

243 THE MADWOMAN OF CHAILLOT

passing a boxful of counterfeit notes. A year later, I saw another such face. It got me a nice berth in the narcotics business. Since then, all I do is to look out for such faces. And now here I am — president of eleven corporations, director of fifty-two companies, and, beginning today, chairman of the board of the international combine in which you have been so good as to accept a post.

fThe Ragpicker passes y sees something under the President’s table^ and stoops to pick it up.)

Looking for something?

THE RAGPICKER. Did you drop this?

THE PRESIDENT. I never drop anything.

THE RAGPICKER. Then this hundred-franc note isn’t yours?

THE PRESIDENT. Givc it here.

(The Ragpicker gives him the note, and goes out.)

THE BARON. Are you sure it’s yours?

THE PRESIDENT. All huudred-franc notes, Baron, are mine.

THE BARON. Mr. President, there’s something I’ve been wanting to ask you. What exactly is the purpose of our new company? Or is that an indiscreet question . . . ?

THE PRESIDENT. Indiscreet? Not a bit. Merely unusual. As far as I know, you’re the first member of a board of directors ever to ask such a question.

THE BARON. Do we plan to exploit a commodity? A utility?

THE PRESIDENT. My dear sir, I haven’t the faintest idea.

THE BARON. But if you don’t know — who does?

THE PRESIDENT. Nobody. And at the moment, it’s becoming just a trifle embarrassing. Yes, my dear Baron, since we are now close business associates, I must confess that for the time being we’re in a little trouble.

THE BARON. I was afraid of that. The stock issue isn’t going well?

THE PRESIDENT. No, no — on the con-

trary. The stock issue is going beautifully.

Yesterday morning at ten o’clock we

offered 5^00,000 shares to the general

public. By 10:05^ they were all snapped

up at par. By 10: 20, when the police

finally arrived, our offices were a sham-

bles . . . Windows smashed — doors torn off their hinges — you never saw anything

so beautiful in your life ! And this morning

our stock is being quoted over the

counter at 124 with no sellers, and the

orders are still pouring in.

THE BARON. But in that case — ^what is

the trouble?

THE PRESIDENT. The trouble is we

have a tremendous capital, and not the

slightest idea of what to do with it.

THE BARON. You mean all those people

are fighting to buy stock in a company

that has no object?

THE PRESIDENT. My dear Baron, do

you imagine that when a subscriber buys

a share of stock, he has any idea of getting

behind a counter or digging a ditch? A

stock certificate is not a tool, like a

shovel, or a commodity, like a pound of

cheese. What we sell a customer is not a

share in a business, but a view of the

Elysian Fields. A financier is a creative

artist. Our function is to stimulate the

imagination. We are poets !

THE BARON. But in Order to stimulate

the imagination, don’t you need some

field of activity?

THE PRESIDENT. Not at all. What you

need for that is a name. A name that will

stir the pulse like a trumpet call, set the

brain awhirl like a movie star, inspire

reverence like a cathedral. United General

International Consolidated ! Of course “that’s

been used. That’s what a corporation

needs.

THE BARON. And do we have such a

name ?

THE PRESIDENT. So far we have only a

blank space. In that blank space a name

must be printed. This name must be a

masterpiece. And if I seem a little nervous

today, it’s because — somehow — I’ve

racked my brains, but it hasn’t come to

me. Oho! Look at that! Just like the

answer to a prayer . . . ! (The Baron turns

and stares in the direction of the Prospector)

You see? There’s one. And what a

beauty !

THE BARON. You mean that girl?

THE PRESIDENT. No, no, not the girl.

That face. You see . . . ? The one that’s

drinking water.

THE BARON. You call that a face?

That’s a tombstone.

244

THE PRESIDENT. It’s a milestone. It’s a

signpost. But is it pointing the way to

steel, or wheat, or phosphates? That’s

what we have to find out. Ah ! He sees me.

He understands. He will be over.

THE BARON. And when he comes . . .?

THE PRESIDENT. He will tell me what

to do.

THE BARON. You mean business is

done this way? You mean, you would

trust a stranger with a matter of this

importance ?

THE PRESIDENT. Baron, I trust neither

my wife, nor my daughter, nor my closest

friend. My confidential secretary has no

idea where I live. But a face like that I

would trust with my inmost secrets.

Though we have never laid eyes on each

other before, that man and I know each

other to the depths of our souls. He’s no

stranger — he’s my brother, he’s myself.

You’ll see. He’ll be over in a minute.

fThe Deaf-Mute enters and passes slowly

among the tables, placing a small envelope

before each customer. He comes to the

President’s table) What is this anyway? A

conspiracy? We don’t want your en-

velopes. Take them away. (The Deaf-Mute

makes a short but pointed speech in sign

language) Waiter, what the devil’s he

saying ?

WAITER. Only Irma understands him.

THE PRESIDENT. Irma? Who’s Irma?

WAITER (calls). Irma! It’s the waitress

inside, sir. Irma!

(Irma comes out. She is twenty. She has the

face and figure of an angel.)

IRMA. Yes?

WAITER. These gentlemen would . . .

THE PRESIDENT. Tell this fellow to get

out of here, for God’s sake! (The Deaf

Mute makes another manual oration) What’s

he trying to say, anyway?

IRMA. He says it’s an exceptionally

beautiful morning, sir . . .

THE PRESIDENT. Who asked him?

IRMA. But, he says, it was nicer before

the gentleman stuck his face in it.

THE PRESIDENT. Call the manager!

(Irma shrugs. She goes back into the restaurant.

The Deaf-Mute walks ojf. Left. Meanwhile a

Shoelace Peddler has arrived.)

PEDDLER. Shoelaces? Postcards?

THE BARON. I think I could use a

shoelace.

THE PRESIDENT. No, nO . . .

PEDDLER. Black? Tan?

THE BARON (showing his shoes) . What

would you recommend?

PEDDLER. Anybody’s guess.

THE BARON. Well, give me one of

each.

THE PRESIDENT (putting a hand on the

Baron’s arm). Baron, although I am your

chairman, I have no authority over your

personal life — none, that is, except to fix

the amount of your director’s fees, and

eventually to assign a motor car for your

use. Therefore, I am asking you, as a

personal favor to me, not to purchase

anything from this fellow.

THE BARON. How Can I resist so

gracious a request? (The Peddler shrugs,

and passes on) But I really don’t under-

stand …. What difference would it

make?

THE PRESIDENT. Look here. Baron.

Now that you’re with us, you must

understand that between this irresponsible

riff-raff and us there is an impenetrable

barrier. We have no dealings whatever

with them.

THE BARON. But without US, the poor

devil will starve.

THE PRESIDENT. No, he won’t. He

expects nothing from us. He has a clien-

tele of his own. He sells shoelaces ex-

clusively to those who have no shoes. Just

as the necktie peddler sells only to those

who wear no shirts. And that’s why these

street hawkers can afford to be insolent,

disrespectful and independent. They

don’t need us. They have a world of their

own. Ah! My broker. Splendid. He’s

beaming. (The Broker walks up and grasps

the President’s hand with enthusiasm)

BROKER. Mr. President! My heartiest

congratulations ! What a day ! What a day !

(The Street Juggler appears. Right. He

removes his coat, folds it carefully, and puts

it on the bench. Then he opens a suitcase,

from which he extracts a number of colored

clubs.)

THE PRESIDENT (presenting the Broker).

Baron Tommard, of our Board of

Directors. My broker. (The Broker bows.

So does the Juggler. The Broker sits down and

HS

signals Jor a drink. The Juggler prepares to

juggle) What’s happened?

BROKER. Listen to this. Ten o’clock

this morning. The market opens. (As he

speaks^ the Juggler provides a visual counter-

part to the Broker’s lineSy his clubs rising and

falling in rhythm to the words) Half million

shares issued at par, par value a hundred,

quoted on the curb at 124 and we start

buying at 126, 127, 129 — and it’s going

up — up — up — (The Juggler’s clubs rise

higher and higher) — 132 — 133 — 138 —

141 — 141 — 141 — 141 . . .

THE BARON. May I ask . . . ?

THE PRESIDENT. No, no — any explana-

tion would only confuse you.

BROKER. Ten forty-five we start

selling short on rumors of a Communist

plot, market bearish . . . 141 — 138 — 133

— 132 — and it’s downn — down — down —

102 — and we start buying back at 93.

Eleven o’clock, rumors denied — 95^ — 98

— loi — 106 — 124 — 141 — and by 11:30

we’ve got it all back — net profit three

and a half million francs.

THE PRESIDENT. Classical. Pure. (The

Juggler bows again. A Little Man leans over

from a near-by table, listening intently, and

trembling with excitement) And how many

shares do we reserve to each member of

the board?

BROKER. Fifty, as agreed.

THE PRESIDENT. Bit Stingy, don’t you

think?

BROKER. All right — three thousand.

THE PRESIDENT. That’s a little better.

(To the Baron) You get the idea?

THE BARON. I’m beginning to get it.

BROKER. And now we come to the

exciting part – . . ( The Juggler prepares to

juggle with balls of jire) Listen carefully :

With i£ percent of our funded capital

under Section 32 I buy ^0,000 United at

36 which I immediately reconvert into

32,000 National Amalgamated two’s

preferred which I set up as collateral on

1^0,000 General Consols which I deposit

against a credit of fifteen billion to buy

Eastern Hennequin which I immediately

turn into Argentine wheat realizing 136

percent of the original investment which

naturally accrues as capital gain and not as

corporate income thus saving twelve

millions in taxes, and at once convert the

2^ percent cotton reserve into lignite,

and as our people swing into action in

London and New York, I beat up the

price on raw silk from 26 to 92 — 114

— 203 — 306 — (The Juggler by now is

juggling hisjireballs in the sky. The balls no

longer return to his hands) 404 . . . (The

Little Man can stand no more. He rushes over

and dumps a sackful oj money on the table)

LITTLE MAN. Here — take it — please,

take it!

BROKER (frigidly). Who is this man?

What is this money?

LITTLE MAN. It’s my life’s savings.

Every cent. I put it all in your hands.

BROKER. Can’t you see we’re busy?

LITTLE MAN. But I beg you . . . It’s my

only chance . . . Please don’t turn me

away,

BROKER. Oh, all right. (He sweeps the

money into his pocket) Well?

LITTLE MAN. I thought — perhaps you’d

give me a little receipt . . .

THE PRESIDENT. My dear man, people

like us don’t give receipts for money. We

take them.

LITTLE MAN. Oh, pardon. Of course.

I was confused. Here it is. (Scribbles a

receipt) Thank you — thank you — thank

you. (He rushes off joyfully . The Street Singer

reappears)

STREET SINGER (sings)

Do you hear, Mademoiselle,

Those musicians of hell ?

THE PRESIDENT. What, again? Why

does he keep repeating those two lines

like a parrot?

WAITER. What else can he do? He

doesn’t know any more and the song’s

been out of print for years .

THE BARON. Couldn’t he sing a song

he knows?

WAITER. He likes this one. He hopes

if he keeps singing the beginning someone

will turn up to teach him the end.

THE PRESIDENT. Tell him to move on.

We don’t know the song.

(The Professor strolls by, swinging his cane.

He overhears.)

PROFESSOR (stops and addresses the

President politely) . Nor do I, my dear sir.

Nor do I. And yet, I’m in exactly the

same predicament. I remember just two

lines of my favorite song, as a child. A

246

mazurka also, in case you’re interested . . .

THE PRESIDENT. I’m not.

PROFESSOR. Why is it, I wonder, that one always forgets the words of a mazurka? I suppose they just get lost in that damnable rhythm. All I remember is:

(He sings) From England to Spain

I have drunk, it was bliss . . .

STREET SINGER (walks over, and picks up

the tune).

Red wine and champagne

And many a kiss.

PROFESSOR. Oh, God! It all comes back to me . . . ! (He sings) Red lips and white hands I have [known

Where the nightingales dwell . . .

THE PRESIDENT (holding his hands to his

ears) . Please — please . . .

STREET SINGER And to each one I’ve whispered, [“My own,”

And to each one, I’ve murmured: [“Farewell.”

THE PRESIDENT. Farewell. Farewell.

STREET SINGER and PROFESSOR (duo) .

But there’s one I shall never forget . .

THE PRESIDENT. This isn’t a cafe. It’s a

circus !

(The two go off^ still singing: ^^ There is one

that’s engraved in my heart.” The Prospector

gets up slowly and walks toward the President’s table. He looks down without a word. There is a tense silence. J

PROSPECTOR. Well?

THE PRESIDENT. I need a name.

PROSPECTOR (nods, with complete compre-

hension) . I need fifty thousand.

THE PRESIDENT. For a Corporation.

PROSPECTOR. For a woman.

THE PRESIDENT. Immediately.

PROSPECTOR. Before evening.

THE PRESIDENT. Something . . .

PROSPECTOR. Unusual?

THE PRESIDENT. Something . . .

PROSPECTOR. Provocative?

THE PRESIDENT. Something . . .

PROSPECTOR. Practical.

THE PRESIDENT. YeS.

PROSPECTOR. Fifty thousand. Cash.

THE PRESIDENT. I’m listening.

PROSPECTOR. International Substrate of

Paris Inc.

THE PRESIDENT ( snaps his fingers ) . That’s

it! (To the Broker) Pay him off. (The

Broker pays with the Little Man’s money)

Now — what does it mean?

PROSPECTOR. It means what it says. I’m a prospector.

THE PRESIDENT (rises). A prospector !

Allow me to shake your hand. Baron. You

are in the presence of one of nature’s

noblemen. Shake his hand. This is Baron

Tommard. (They shake hands) It is this

man, my dear Baron, who smells out in

the bowels of the earth those deposits of

metal or liquid on which can be founded

the only social unit of which our age is

capable — the corporation. Sit down,

please. (They all sit) And now that we

have a name . . .

PROSPECTOR. You need a property.

THE PRESIDENT. Precisely.

PROSPECTOR. I have one.

THE PRESIDENT. A claim?

PROSPECTOR. Terrific.

THE PRESIDENT. Foreign?

PROSPECTOR. French.

THE BARON. In Indo- China?

BROKER. Morocco?

THE PRESIDENT. In France?

PROSPECTOR (matter of fact). In Paris.

THE PRESIDENT. In Paris ? You’ve been

prospecting in Paris?

THE BARON. FoT women, no doubt.

THE PRESIDENT. FOT art?

BROKER. For gold?

PROSPECTOR. Oil.

BROKER. He’s crazy.

THE PRESIDENT. Sh ! He’s inspired.

PROSPECTOR. You think I’m crazy.

Well, they thought Columbus was crazy.

THE BARON. Oil in Paris?

BROKER. But how is it possible?

PROSPECTOR. It’s not Only possible.

It’s certain.

THE PRESIDENT. Tell US.

PROSPECTOR. You don’t know, my

dear sir, what treasures Paris conceals.

Paris is the least prospected place in the

world. We’ve gone over the rest of the

planet with a fine-tooth comb. But has

anyone ever thought of looking for oil in

Paris? Nobody. Before me, that is.

THE PRESIDENT. Genius !

PROSPECTOR. No. Just a practical man.

I use my head.

THE MADWOMAN OF CHAILLOT

247

THE BARON. But why has nobody ever thought of this before ?

PROSPECTOR. The treasures of the

earth, my dear sir, are not easy to find nor

to get at. They are invariably guarded by

dragons. Doubtless there is some reason

for this. For once vv^e’ve dug out and

consumed the internal ballast of the

planet, the chances are it w^ill shoot off on

some irresponsible tangent and smash

itself up in the sky. Well, that’s the risk

we take. Anyway, that’s not my business.

A prospector has enough to worry about.

THE BARON. I know — snakes — taran-

tulas — fleas . . .

PROSPECTOR. Worse than that, sir.

Civilization.

THE PRESIDENT. Does that annoy you?

PROSPECTOR. Civilization gets in our

way all the time. In the first place, it

covers the earth with cities and towns

which are damned awkward to dig up

when you want to see what’s underneath.

It’s not only the real-estate people — you

can always do business with them — it’s

human sentimentality. How do you do

business with that ?

THE PRESIDENT. I see what you mean.

PROSPECTOR. They say that where we

pass, nothing ever grows again. What of

it ? Is a park any better than a coal mine ?

What’s a mountain got that a slag pile

hasn’t? What would you rather have in

your garden — an almond tree or an oil

well?

THE PRESIDENT. Well . . .

PROSPECTOR. Exactly. But what’s the

use of arguing with these fools ? Imagine

the choicest place you ever saw for an

excavation, and what do they put there?

A playground for children ! Civilization !

THE PRESIDENT. Just show US the point

where you want to start digging. We’ll do

the rest. Even if it’s in the middle of the

Louvre. Where’s the oil?

PROSPECTOR. Perhaps you think it’s

easy to make an accurate fix in an area

like Paris where everything conspires to

put you off the scent? Women — perfume

— flowers — history. You can talk all you

like about geology, but an oil deposit,

gentlemen, has to be smelled out. I have a

good nose. I go further. I have a phe-

nomenal nose. But the minute I get the right whiff — the minute I’m on the scent

— a fragrance rises from what I take to be

the spiritual deposits of the past — and

I’m completely at sea. Now take this very

point, for example, this very spot.

THE BARON. You mean — right here in Chaillot?

PROSPECTOR. Right under here.

THE PRESIDENT. Good heavens !

(He looks under his chair. J

PROSPECTOR. It’s taken me months to locate this spot.

THE BARON. But what in the world makes you think . . . ?

PROSPECTOR. Do you know this place, Baron ?

THE BARON. Well, I’ve been sitting here for thirty years.

PROSPECTOR. Did you ever taste the water ?

THE BARON. The Water ? Good God, no !

PROSPECTOR. It’s plain to see that you

are no prospector! A prospector. Baron,

is addicted to water as a drunkard to wine.

Water, gentlemen, is the one substance

from which the earth can conceal nothing.

It sucks out its innermost secrets and

brings them to our very lips. Well —

beginning at Notre Dame, where I first

caught the scent of oil three months ago,

I worked my way across Paris, glassful by

glassful, sampling the water, until at last

I came to this cafe. And here — ^just two

days ago — I took a sip. My heart began to

thump. Was it possible that I was

deceived ? I took another, a third, a fourth,

a fifth. I was trembling like a leaf. But

there was no mistake. Each time that I

drank, my taste-buds thrilled to the most

exquisite flavor known to a prospector —

the flavor of — (With utmost lyricism)

Petroleum !

THE PRESIDENT. Waiter! Some water

and four glasses. Hurry. This round,

gentlemen, is on me. And as a toast — I

shall propose International Substrate of

Paris, Incorporated. (The Waiter brings

a decanter and the glasses. The President pours

out the water amid profound silence. They

taste it with the air of connoisseurs savoring

something that has never before passed human

lips. Then they look at each other doubtfully.

The Prospector pours himself a second glass and drinks it off) Well . . .

248

BROKER. Ye-es . . .

THE BARON. Mm . . .

PROSPECTOR. Get it?

THE BARON. Tastcs quecr.

PROSPECTOR. That’s it. To the un-

practiced palate it tastes queer. But to the

taste-buds of the expert — ah !

THE BARON. Still, there’s one thing I

don’t quite understand . . .

PROSPECTOR. Yes?

THE BARON. This cafe doesn’t have its

own well, does it?

PROSPECTOR. Of course not. This is Paris water.

BROKER. Then why should it taste

different here than anywhere else?

PROSPECTOR. Because, my dear sir,

the pipes that carry this water pass deep

through the earth, and the earth just here

is soaked with oil, and this oil permeates

the pores of the iron and flavors the water

it carries. Ever so little, yes — but quite

enough to betray its presence to the

sensitive tongue of the specialist.

THE BARON. 1 SeC.

PROSPECTOR. I don’t say everyone is

capable of tasting it. No. But I — I can

detect the presence of oil in water that

has passed within fifteen miles of a

deposit. Under special circumstances,

twenty.

THE PRESIDENT. Phenomenal !

PROSPECTOR. And so here I am with

the greatest discovery of the age on my

hands— but the blasted authorities won’t

let me drill a single well unless I show

them the oil ! Now how can I show them

the oil unless they let me dig? Completely

stymied! Eh?

THE PRESIDENT. What? A man like

you?

PROSPECTOR. That’s what they think.

That’s what they want. Have you noticed

the strange glamor of the women this

morning? And the quality of the sun-

shine? And this extraordinary convo-

cation of vagabonds buzzing about pro-

tectively like bees around a hive? Do you

know why it is? Because they know. It’s

a plot to distract us, to turn us from our

purpose. Well, let them try. I know

there’s oil here. And I’m going to dig it

up, even if I . . . (He smiles) Shall I tell

you my little plan?

THE PRESIDENT. By all mcans.

PROSPECTOR. Well . . . For heaven’s

sake, what’s that?

(At this pointy the Madwoman enters. She is

dressed in the grand Jashion of l886 in a

taffeta skirt with an immense train — which she has gathered up by means of a clothespin — ancient button shoes, and a hat in the style of Marie Antoinette. She wears a lorgnette on a

chain, and an enormous cameo pin at her

throat. In her hand she carries a small basket.

She walks in with great dignity, extracts a

dinner bell from the bosom of her dress, and

rings it sharply. Irma appears. J

COUNTESS. Are my bones ready, Irma?

IRMA. There won’t be much today,

Countess. We had broilers. Can you

wait? While the gentleman inside finishes

eating ?

COUNTESS. And my gizzard ?

IRMA. I’ll try to get it away from him.

COUNTESS. If he eats my gizzard, save

me the giblets. They will do for the

tomcat that lives under the bridge. He

likes a few giblets now and again.

IRMA. Yes, Countess.

(Irma goes back into the cafe. The Countess

takes a few steps and stops in front of the

President’s table. She examines him with

undisguised disapproval. J

THE PRESIDENT. Waiter. Ask that

woman to move on.

WAITER. Sorry, sir. This is her cafe.

THE PRESIDENT. Is shc the manager of

the cafe?

WAITER. She’s the Madwoman of

Chaillot.

THE PRESIDENT. A Madwoman ? She’s

mad?

WAITER. Who says she’s mad?

THE PRESIDENT. You just Said SO your-

self.

WAITER. Look, sir. You asked me who

she was. And I told you. What’s mad

about her? She’s the Madwoman of

Chaillot.

THE PRESIDENT. Call a policcman.

(The Countess whistles through her fingers.

At once, the Doorman runs out of the cafe. He

has three scarves in his hands.)

COUNTESS. Have you found it? My

feather boa?

DOORMAN. Not yet, Countess. Three

scarves. But no boa.

249

COUNTESS. It’s five years since I lost it.

Surely you’ve had time to find it.

DOORMAN. Take one of these, Count-

ess. Nobody’s claimed them.

COUNTESS. A boa like that doesn’t

vanish, you know. A feather boa nine feet

long!

DOORMAN. Hovs^ about this blue one?

COUNTESS. With my pink ruffle and

my green veil? You’re joking ! Let me see

the yellow^. (She tries it on) How does it

look?

DOORMAN. Terrific.

(With a magnificent gesture, she flings the

scarf about her, upsetting the president’ s glass and drenching his trousers with water. She stalks off without a glance at him.)

THE PRESIDENT. Waiter! I’m making a

complaint.

WAITER. Against whom?

THE PRESIDENT. Against her! Against

you ! The whole gang of you ! That singer !

That shoelace peddler! That female

lunatic ! Or whatever you call her !

THE BARON. Calm yourself, Mr.

President . . .

THE PRESIDENT. I’ll do nothing of the

sort! Baron, the first thing we have to do

is to get rid of these people ! Good

heavens, look at them ! Every size, shape,

color and period of history imaginable.

It’s utter anarchy ! I tell you, sir, the only

safeguard of order and discipline in the

modern world is a standardized worker

with interchangeable parts. That would

solve the entire problem of management.

Here, the manager . . . And there — one

composite drudge grunting and sweating

all over the world. Just we two. Ah, how

beautiful ! How easy on the eyes ! How

restful for the conscience !

THE BARON. Yes, ycs — of course.

THE PRESIDENT. Order. Symmetry.

Balance. But instead of that, what? Here

in Chaillot, the very citadel of manage-

ment, these insolent phantoms of the past

come to beard us with their raffish in-

dividualism — with the right of the

voiceless to sing, of the dumb to make

speeches, of trousers to have no seats and

bosoms to have dinner bells !

THE BARON. But, after all, do these

people matter?

THE PRESIDENT. My dear sir, wherever the poor are happy, and the servants are proud, and the mad are respected, our power is at an end. Look at that! That

waiter! That madwoman! That flower girl! Do I get that sort of service? And suppose that I — president of twelve

corporations and ten times a millionaire — were to stick a gladiolus in my button-hole and start yelling — (He tinkles his spoon in a glass violently, yelling) Are my bones ready, Irma?

THE BARON (reprovingly). Mr. President . . .

(People at the adjoining tables turn and stare

with raised eyebrows. The Waiter starts to

come over.)

THE PRESIDENT. YoU SCC? Now.

PROSPECTOR. We were discussing my

plan.

THE PRESIDENT. Ah ycs, youT plan.

(He glances in the direction of the Mad-

woman s table) Careful — she’s looking at

us.

PROSPECTOR. Do you know what a

bomb is?

THE PRESIDENT. I’m told they cxplodc.

PROSPECTOR. Exactly. You see that

white building across the river. Do you

happen to know what that is ?

THE PRESIDENT. I do not.

PROSPECTOR. That’s the office of the

City Architect. That man has stubbornly

refused to give me a permit to drill for

oil anywhere within the limits of the city

of Paris. I’ve tried everything with him —

influence, bribes, threats. He says I’m

crazy. And now . . .

THE PRESIDENT. Oh, my God ! What is

this one trying to sell us ?

(A little Old Man enters left, and doffs his hat

politely. He is somewhat ostentatiously

respectable — gloved, pomaded, and carefully

dressed, with a white handkerchief peeping out

oj his breast pocket.)

DR. JADIN. Nothing but health, sir. Or

rather the health of the feet. But

remember — as the foot goes, so goes the

man. May I present myself . . . ? Dr.

Gaspard Jadin, French Navy, retired.

Former specialist in the extraction of

ticks and chiggers. At present special-

izing in the extraction of bunions and

corns. In case of sudden emergency.

Martial the waiter will furnish my home

2^0

address. My office is here, second row,

third table, week days, twelve to five.

Thank you very much.

(^He sits at his table. J

WAITER. Your vermouth, Doctor?

DR. JADIN. My vermouth. My ver-

mouths. How are your gallstones today,

Martial ?

WAITER. Fine. Fine. They rattle like

anything.

DR. JADIN. Splendid. (He spies the

Countess) Good morning, Countess. How’s

the floating kidney? Still afloat? (She nods

graciously) Splendid. Splendid. So long as

it floats, it can’t sink.

THE PRESIDENT. This is impossible !

Let’s go somewhere else.

PROSPECTOR. No. It’s nearly noon.

THE PRESIDENT. Yes. It IS. Five to

twelve.

PROSPECTOR. In five minutes’ time

you’re going to see that City Architect

blown up, building and all — boom !

BROKER. Are you serious?

PROSPECTOR. That imbecile has no

one to blame but himself. Yesterday noon,

he got my ultimatum — he’s had twenty-

four hours to think it over. No permit?

All right. Within two minutes my agent

is going to drop a little package in his

coal bin. And three minutes after that,

precisely at noon . . .

THE BARON. You prospectors certainly

use modern methods.

PROSPECTOR. The method may be

modern. But the idea is old. To get at the

treasure, it has always been necessary to

slay the dragon. I guarantee that after

this, the City Architect will be more

reasonable. The new one, I mean.

THE PRESIDENT. Don’t you think we’re

sitting a little close for comfort?

PROSPECTOR. Oh no, no. Don’t worry.

And, above all, don’t stare. We may be

watched. (A clock strikes) Why, that’s

noon. Something’s wrong! Good God!

What’s this? (A Policeman staggers in

bearing a lijeless body on his shoulders in the

manner prescribed as ^^The Fireman s Lijt^^ )

It’s Pierre! My agent! (He walks over with

affected nonchalance) I say. Officer, what’s

that you’ve got?

POLICEMAN. Drowned man.

(He puts him down on the bench.)

WAITER . He ‘snot drowned . His clothes

are dry. He’s been slugged.

POLICEMAN. Slugged is also correct.

He was just jumping off the bridge when

1 came along and pulled him back. I

slugged him, naturally, so he wouldn’t

drag me under. Life Saving Manual,

Rule £: “In cases where there is danger

of being dragged under, it is necessary to

render the subject unconscious by means

of a sharp blow.” He’s had that.

(He loosens the clothes and begins applying

artificial respiration.)

PROSPECTOR. The stupid idiot! What

the devil did he do with the bomb?

That’s what comes of employing

amateurs !

THE PRESIDENT. You don’t think he’ll

give you away ?

PROSPECTOR. Don’t worry. (He walks

over to the policeman) Say, what do you

think you’re doing?

POLICEMAN. Lifesaving. Artificial

respiration. First aid to the drowning.

PROSPECTOR. But he’s not drowning.

POLICEMAN. But he thinks he is.

PROSPECTOR. You’ll never bring him

round that way, my friend. That’s meant

for people who drown in water. It’s no

good at all for those who drown without

water.

POLICEMAN. What am I supposed do?

I’ve just been sworn in. It’s my first day

on the beat. I can’t afford to get in

trouble. I’ve got to go by the book.

PROSPECTOR. Perfectly simple. Take

him back to the bridge where you found

him and throw him in. Then you can save

his life and you’ll get a medal. This way,

you’ll only get fined for slugging an

innocent man.

POLICEMAN. What do you mean,

innocent? He was just going to jump

when I grabbed him.

PROSPECTOR. Have you any proof of

that?

POLICEMAN. Well, I saw him.

PROSPECTOR. Written proof? Wit-

nesses ?

POLICEMAN. No, but . . .

PROSPECTOR. Then don’t waste time

arguing. You’re in trouble. Quick —

before anybody notices — throw him in

and dive after him. It’s the only way out.

2SI

POLICEMAN. But I don’t swim.

THE PRESIDENT. You’ll Icam how on

the way down. Before you were bom, did

you know how to breathe ?

POLICEMAN (convinced) . All right.

Here we go.

(He starts lifting the body.)

DR. JADIN. One moment, please. I

don’t like to interfere, but it’s my

professional duty to point out that medical

science has definitely established the fact

of intra-uterine respiration. Conse-

quently, this policeman, even before he

was bom, knew not only how to breathe

but also how to cough, hiccup and belch.

THE PRESIDENT. Supposc he did — how

does it concern you?

DR. JADIN. On the other hand, medical

science has never established the fact of

intra-uterine swimming or diving. Under

the circumstances, we are forced to the

opinion, Officer, that if you dive in you

will probably drown.

POLICEMAN. You think so?

PROSPECTOR, who asked you for an

opinion?

THE PRESIDENT. Pay no attention to

that quack, Officer.

DR. JADIN. Quack, sir?

PROSPECTOR. This is not a medical

matter. It’s a legal problem. The officer

has made a grave error. He’s new. We’re

trying to help him.

BROKER. He’s probably afraid of the

water.

POLICEMAN. Nothing of the sort.

Officially, I’m afraid of nothing. But I

always follow doctor’s orders.

DR. JADIN. You see. Officer, when a

child is born . . .

PROSPECTOR. Now, what does he care

about when a child is born? He’s got a

dying man on his hands . . . Officer, if

you want my advice . . .

POLICEMAN. It so happens, I care a lot

about when a child is bom. It’s part of

my duty to aid and assist any woman in

childbirth or labor.

THE PRESIDENT. Can you imagine !

POLICEMAN. Is it true. Doctor, what

they say, that when you have twins, the

first bom is considered to be the

youngest ?

DR. JADIN. Quite correct. And what’s more, if the twins happen to be bom at midnight on December 31st, the older is a whole year younger. He does his military service a year later. That’s why you have to keep your eyes open. And that’s the reason why a queen always gives birth before witness . . .

POLICEMAN. God ! The things a police-

man is supposed to know! Doctor, what

does it mean if, when I get up in the

morning sometimes . . .

PROSPECTOR (nudging the President

meaning juUj ) . The old woman . . .

BROKER. Come on. Baron.

THE PRESIDENT. I think wc’d better all

run along.

PROSPECTOR. Leave him to me.

THE PRESIDENT. I’ll scc you later.

(The President steals off with the Broker and

the Baron.)

POLICEMAN (still in conference with Dr.

Jadin). But what’s really worrying me,

Doctor, is this — don’t you think it’s a bit

risky for a man to marry after forty-five?

(The Broker runs in breathlessly . )

BROKER. Officer! Officer!

POLICEMAN, what’s the trouble?

BROKER. Quick! Two women are

calling for help — on the sidewalk —

Avenue Wilson!

POLICEMAN. Two womcn at once?

Standing up or lying down?

BROKER. You’d better go and see.

Quick !

PROSPECTOR. You’d better take the

Doctor with you.

POLICEMAN. Come along, Doctor,

come along . . . (Pointing to Pierre) Tell

him to wait till I get back. Come along.

Doctor.

(He runs out^ the Doctor following. The

Prospector moves over toward Pierre^ but Irma

crosses in front of him and takes the boj^s

hand.)

IRMA. How beautiful he is ! Is he dead,

Martial ?

WAITER (handing her a pocket mirror).

Hold this mirror to his mouth. If it clouds

over . . .

IRMA. It clouds over.

WAITER . He ‘ s alive .

(He holds out his hand for the mirror.)

IRMA. Just a sec — (She rubs it clean and

looks at herself intently. Before handing it

2^2

back, she fixes her hair and applies her lip-

stick. Meanwhile the Prospector tries to get

around the other side, hut the Countess eagle

eye drives him off. He shrugs his shoulders and

exits with the Baron) Oh, look — he’s

opened his eyes !

(Pierre opens his eyes, stares intently at Irma

and closes them again with the expression oj a

man who is among the angels.)

PIERRE (murmurs) . Oh ! How beautiful !

VOICE (from within the cafe) . Irma !

IRMA. Coming. Coming. (She goes in,

not without a certain reluctance. The Countess

at once takes her place on the bench, and also

the young man s hand. Pierre sits up suddenly,

and fnds himself staring, not at Irma, but

into the very peculiar face of the Countess.

His expression changes.)

COUNTESS. You’re looking at my iris?

Isn’t it beautiful?

PIERRE. Very. (He drops back, ex-

hausted.)

COUNTESS. The Sergeant was good

enough to say it becomes me. But I no

longer trust his taste. Yesterday, the

flower girl gave me a lily, and he said it

didn’t suit me.

viEBJR.’E (weakly) . It’s beautiful.

COUNTESS. He’ll be very happy to

know that you agree with him. He’s really

quite sensitive. (She calls) Sergeant!

PIERRE. No, please — don’t call the

police.

COUNTESS. But I must. I think I hurt

his feelings.

PIERRE. Let me go, Madame.

COUNTESS. No, no. Stay where you are.

Sergeant !

(Pierre struggles weakly to get up.)

PIERRE. Please let me go.

COUNTESS. I’ll do nothing of the sort.

When you let someone go, you never see

him agam. I let Charlotte Mazumet go.

I never saw her again.

PIERRE. Oh, my head.

COUNTESS. I let Adolphe Bertaut go.

And I was holding him. And I never saw

him again.

PIERRE. Oh, God!

COUNTESS. Except once. Thirty years later. In the market. He had changed a great deal — he didn’t know me. He sneaked a melon from right under my nose, the only good one of the year. Ah, here we are. Sergeant!

(The Police Sergeant comes in with importance.)

SERGEANT. I’m in a hurry. Countess.

COUNTESS. With regard to the iris.

This young man agrees with you. He says

it suits me.

SERGEANT (going). There’s a man

drowning in the Seine.

COUNTESS. He’s not drowning in the

Seine. He’s drowning here.* Because I’m

holding him tight — as I should have held

Adolphe Bertaut. But if I let him go, I’m

sure he will go and drown in the Seine.

He’s a lot better looking than Adolphe

Bertaut, wouldn’t you say?

(Pierre sighs deeply.)

SERGEANT. How would I know?

COUNTESS. I’ve shown you his photo-

graph. The one with the bicycle.

SERGEANT. Oh, yes. The one with the

harelip.

COUNTESS. I’ve told you a hundred

times! Adolphe Bertaut had no harelip.

That was a scratch in the negative. (The

Sergeant takes out his notebook and pencil)

What are you doing?

SERGEANT. I am taking down the

drowned man’s name, given name and

date of birth.

COUNTESS. You think that’s going to

stop him from jumping in the river?

Don’t be silly. Sergeant. Put that book

away and try to console him.

SERGEANT. I should try and console

him?

COUNTESS. When people want to die,

it is your job as a guardian of the state to

speak out in praise of life. Not mine.

SERGEANT. I should spcak out in praise

of life?

COUNTESS. I assume you have some motive for interfering with people’s attempts to kill each other, and rob each other, and run each other over? If you believe that life has some value, tell him what it is. Go on.

SERGEANT. Well, all right. Now look, young man . . .

COUNTESS. His name is Roderick.

PIERRE. My name is not Roderick.

COUNTESS. Yes, it is. It’s noon. At

noon all men become Roderick.

THE MADWOMAN OF CHAILLOT H3

SERGEANT. Except Adolphe Bertaut.

COUNTESS. In the days of Adolphe

Bertaut, we were forced to change the

men when we got tired of their names.

Nowadays, we’re more practical — each

hour on the hour all names are auto-

matically changed. The men remain the

same. But you’re not here to discuss

Adolphe Bertaut, Sergeant. You’re here

to convince the young man that life is

worth living.

PIERRE. It isn’t.

SERGEANT. Quict. Now then — what

was the idea of jumping off the bridge,

anyway ?

COUNTESS. The idea was to land in the

river. Roderick doesn’t seem to be at all

confused about that.

SERGEANT. Now how Can I convince

anybody that life is worth living if you

keep interrupting all the time ?

COUNTESS. I’ll be quiet.

SERGEANT. First of all, Mr. Roderick,

you have to realize that suicide is a crime

against the state. And why is it a crime

against the state ? Because every time any-

body commits suicide, that means one

soldier less for the army, one taxpayer

less for the . . .

COUNTESS. Sergeant, isn’t there some-

thing about life that you really enjoy?

SERGEANT. That I enjoy?

COUNTESS. Well, surely, in all these

years, you must have found something

worth living for. Some secret pleasure,

or passion. Don’t blush. Tell him about it.

SERGEANT. Who’s blushing? Well,

naturally, yes — I have my passions — like

everybody else. The fact is, since you

ask me — I love — to play — casino. And if

the gentleman would like to join me, by

and by when I go off duty, we can sit

down to a nice little game in the back

room with a nice cold glass of beer. If he

wants to kill an hour, that is.

COUNTESS. He doesn’t want to kill an

hour. He wants to kill himself. Well? Is

that all the police force has to offer by

way of earthly bliss ?

SERGEANT. Huh? You mean — (He jerks

a thumb in the direction of the pretty Blonde^

who has just been joined by a Brunette of the

same stamp) Paulette? (The young man

groans)

COUNTESS. You’re not earning your

salary, Sergeant. I defy anybody to stop

dying on your account.

SERGEANT. Go ahead, if you can do any

better. But you won’t find it easy.

COUNTESS. Oh, this is not a desperate

case at all. A young man who has just

fallen in love with someone who has

fallen in love with him !

PIERRE. She hasn’t. How could she?

COUNTESS. Oh, yes, she has. She was

holding your hand, just as I’m holding it,

when all of a sudden . . . Did you ever

know Marshal Canrobert’s niece?

SERGEANT. How could he know

Marshal Canrobert’s niece?

COUNTESS. Lots of people knew her —

when she was alive. (Pierre begins to struggle

energetically) No, no, Roderick — stop —

stop!

SERGEANT. You scc ? You won’t do

any better than I did.

COUNTESS. No? Let’s bet. I’ll bet my

iris against one of your gold buttons.

Right? — Roderick, I know very well why

you tried to drown yourself in the river.

PIERRE. You don’t at all.

COUNTESS. It’s because that Prospector

wanted you to commit a horrible crime.

PIERRE. How did you know that?

COUNTESS. He stole my boa, and now

he wants you to kill me.

PIERRE. Not exactly.

COUNTESS. It wouldn’t be the first

time they’ve tried it. But I’m not so easy

to get rid of, my boy, oh, no . . .

Because . . .

(The Doorman rides in on his bicycle. He

winks at the Sergeant, who has now seated

himself while the Waiter serves him a beer.)

DOORMAN. Take it easy. Sergeant.

SERGEANT. I’m busy saving a drowning

man.

COUNTESS. They can’t kill me because — I have no desire to die.

PIERRE. You’re fortunate.

COUNTESS. To be alive is to be

fortunate, Roderick. Of course, in the

morning, when you first awake, it does

not always seem so very gay. When you

take your hair out of the drawer, and your

teeth out of the glass, you are apt to feel

a little out of place in this world.

Especially if you’ve just been dreaming that you’re a little girl on a pony looking

for strawberries in the woods. But all you

need to feel the call of life once more is a

letter in your mail giving you your

schedule for the day — your mending,

your shopping, that letter to your grand-

mother that you never seem to get around

to. And so, when you’ve washed your

face in rosewater, and powdered it — not

with this awful rice-powder they sell

nowadays, which does nothing for the

skin, but with a cake of pure white

starch — and put on your pins, your rings,

your brooches, bracelets, earrings and

pearls — in short, when you are dressed

for your morning coffee — and have had a

good look at yourself — not in the glass,

naturally — it lies — but in the side of the

brass gong that once belonged to Admiral

Courbet — then, Roderick, then you’re

armed, you’re strong, you’re ready — you

can begin again.

(Pierre is listening now intently. There are

tears in his ejes.J

PIERRE. Oh, Madame . . . ! Oh, Ma-

dame . . . !

COUNTESS. After that, everything is

pure delight. First the morning paper.

Not, of course, these current sheets full

of lies and vulgarity. I always read the

Gaulois, the issue of March 2 2, 1903. It’s

by far the best. It has some delightful

scandal, some excellent fashion notes, and,

of course, the last-minute bulletin on the

death of Leonide Leblanc. She used to

live next door, poor woman, and when I

learn of her death every morning, it gives

me quite a shock. I’d gladly lend you my

copy, but it’s in tatters.

SERGEANT. Couldn’t we find him a

copy in some library?

COUNTESS. I doubt it. And so, when

you’ve taken your fruit salts — not in

water, naturally — no matter what they

say, it’s water that gives you gas — but

with a bit of spiced cake — then in sunlight

or rain, Chaillot calls. It is time to dress

for your morning walk. This takes much

longer, of course — without a maid, im-

possible to do it under an hour, what with

your corset, corset-cover and drawers all

of which lace or button in the back. I

asked Madame Lanvin, a while ago, to fit

the drawers with zippers. She was quite charming, but she declined. She thought it would spoil the style.

(The Deaf- Mute comes in.)

WAITER. I know a place where they put zippers on anything.

(The Ragpicker enters. J

COUNTESS. I think Lanvin knows best.

But I really manage very well. Martial.

What I do now is, I lace them up in front,

then twist them around to the back. It’s

quite simple, really. Then you choose a

lorgnette, and then the usual fruitless

search for the feather boa that the

prospector stole — I know it was he : he

didn’t dare look me in the eye — and then

all you need is a rubber band to slip

around your parasol — I lost the catch the

day I struck the cat that was stalking the

pigeon — it was worth it — ah, that day I

earned my wages !

THE RAGPICKER. Countess, if you can

use it, I found a nice umbrella catch the

other day with a cat’s eye in it.

COUNTESS. Thank you. Ragpicker.

They say these eyes sometimes come to

life and fill with tears. I’d be afraid . . .

PIERRE. Go on, Madame, go on . . .

COUNTESS. Ah! So life is beginning to

interest you, is it? You see how beautiful

it is?

PIERRE. What a fool I’ve been !

COUNTESS. Then, Roderick, I begin

my rounds. I have my cats to feed, my

dogs to pet, my plants to water. I have to

see what the evil ones are up to in the

district — those who hate people, those

who hate plants, those who hate animals.

I watch them sneaking off in the morning

to put on their disguises — to the baths,

to the beauty parlors, to the barbers. But

they can’t deceive me. And when they

come out again with blonde hair and false

whiskers, to pull up my flowers and

poison my dogs, I’m there, and I’m ready.

All you have to do to break their power is

to cut across their path from the left.

That isn’t always easy. Vice moves swiftly.

But I have a good long stride and I

generally manage . . . Right, my friends ?

(The Waiter and the Ragpicker nod their

heads with evident approval) Yes, the

flowers have been marvelous this year.

And the butcher’s dog on the Rue Bizet,

THE MADWOMAN OF CHAILLOT ^55

Iin spite of that wretch that tried to poison

him, is friskier than ever . . .

SERGEANT. That dog had better look

out. He has no Hcense.

COUNTESS. He doesn’t seem to feel the

need for one.

THE RAGPICKER. The Duchess de la

Rochefoucauld’s whippet is getting aw-

fully thin …

COUNTESS. What can I do? She bought

that dog full grown from a kennel where

they didn’t know his right name. A dog

without his right name is bound to get thin .

THE RAGPICKER. I’ve got a friend who

knows a lot about dogs — an Arab . . .

COUNTESS. Ask him to call on the

Duchess. She receives Thursdays, five to

seven. You see, then, Roderick. That’s

life. Does it appeal to you now?

PIERRE. It seems marvelous.

COUNTESS. Ah! Sergeant. My button.

(The Sergeant gives her his button and goes

off. At this point the Prospector enters) That’s

only the morning. Wait till I tell you

about the afternoon !

PROSPECTOR. All right, Pierre. Come

along now.

PIERRE. I’m perfectly all right here.

PROSPECTOR. I said, come along now,

PIERRE (to the Countess) . I’d better go.

Madame.

COUNTESS. No.

PIERRE. It’s no use. Please let go my

hand.

PROSPECTOR. Madame, will you oblige

me by letting my friend go ?

COUNTESS. I will not oblige you in any

way.

PROSPECTOR. All right. Then I’ll

oblige you . . . !

(He tries to push her away. She catches up a

soda water siphon and squirts it in his face.)

PIERRE. Countess . . .

COUNTESS. Stay where you are. This

man isn’t going to take you away. In the

first place, I shall need you in a few

minutes to take me home. I’m all alone

here and I’m very easily frightened.

(The Prospector makes a second attempt to drag

Pierre away . The Countess cracks him over the

skull with the siphon. They join battle. The

Countess whistles. The Doorman comes^ then

the other Vagabonds, and lastly the Police

Sergeant.)

PROSPECTOR. Officer! Arrest this

woman !

SERGEANT. What’s the trouble here?

PROSPECTOR. She refuses to let this

man go.

SERGEANT. Why should she ?

PROSPECTOR. It’s against the law for a

woman to detain a man on the street.

IRMA. Suppose it’s her son whom she’s

found again after twenty years ?

THE RAGPICKER (gallantly). Or her

long-lost brother? The Countess is not

so old.

PROSPECTOR. Officer, this is a clear

case of disorderly conduct.

(The DeaJ-Mute interrupts with frantic

signals.)

COUNTESS. Irma, what is the Deaf-

Mute saying?

IRMA (interpreting) . The young man is

in danger of his life. He mustn’t go with

him.

PROSPECTOR. What does he know ?

IRMA. He knows everything.

PROSPECTOR. Officer, I’ll have to take

your number.

COUNTESS. Take his number. It’s 2133.

It adds up to nine. It will bring you luck.

SERGEANT. Countess, between our-

selves, what are you holding him for,

anyway ?

COUNTESS. I’m holding him because

it’s very pleasant to hold him. I’ve never

really held anybody before, and I’m

making the most of it. And because so

long as / hold him, he’s free.

PROSPECTOR. Pierre, I’m giving you

fair warning . . .

COUNTESS. And I’m holding him be-

cause Irma wants me to hold him. Be-

cause if I let him go, it will break her

heart.

IRMA. Oh, Countess !

SERGEANT (to the Prospector) . All right,

you — move on. Nobody’s holding you.

You’re blocking traffic. Move on.

PROSPECTOR (menacingly) . I have your

number. (And murderously, to Pierre) You’ll

regret this, Pierre.

(Exit Prospector.)

PIERRE. Thank you. Countess.

COUNTESS. They’re blackmailing you,

are they? (Pierre nods) What have you

done? Murdered somebody?

256 JEAN GIRAUDOUX

PIERRE. No.

COUNTESS. Stolen something?

PIERRE. No.

COUNTESS. What then?

PIERRE. I forged a signature.

COUNTESS. Whose signature?

PIERRE. My father’s. To a note.

COUNTESS. And this man has the paper,

I suppose?

PIERRE. He promised to tear it up, if I

did what he wanted. But I couldn’t do it.

COUNTESS. But the man is mad! Does

he really want to destroy the whole

neighborhood?

PIERRE. He wants to destroy the whole

city.

COUNTESS (laughs). Fantastic.

PIERRE. It’s not funny, Countess. He

can do it. He’s mad, but he’s powerful,

and he has friends. Their machines are

already drawn up and waiting. In three

months’ time you may see the city

covered by a forest of derricks and drills.

COUNTESS. But what are they looking

for? Have they lost something?

PIERRE. They’re looking for oil.

They’re convinced that Paris is sitting on

a lake of oil.

COUNTESS. Suppose it is. What harm

does it do?

PIERRE. They want to bring the oil to

the surface, Countess.

COUNTESS (laughs). How silly! Is that

a reason to destroy a city? What do they

want with this oil ?

PIERRE. They want to make war.

Countess.

COUNTESS. Oh, dear, let’s forget about

these horrible men. The world is

beautiful. It’s happy. That’s how God

made it. No man can change it.

WAITER. Ah, Countess, if you only

knew …

COUNTESS. If I only knew what?

WAITER. Shall we tell her now? Shall

we tell her?

COUNTESS. What is it you are hiding

from me?

THE RAGPICKER. Nothing, Countess.

It’s you who are hiding.

WAITER. You tell her. You’ve been a

pitchman. You can talk.

ALL. Tell her. Tell her. Tell her.

COUNTESS. You’re frightening me, my

friends. Go on. I’m listening.

THE RAGPICKER. Countcss, there was a

time when old clothes were as good as

new — in fact, they were better. Because

when people wore clothes, they gave

something to them. You may not believe

it, but right this minute, the highest-

priced shops in Paris are selling clothes

that were thrown away thirty years ago.

They’re selling them for new. That’s how

good they were.

COUNTESS. Well?

THE RAGPICKER. Countcss, there was

a time when garbage was a pleasure. A

garbage can was not what it is now. If it

smelled a little strange, it was because it

was a little confused — there was every-

thing there — sardines, cologne, iodine,

roses. An amateur might jump to a wrong

conclusion. But to a professional — it was

the smell of God’s plenty.

COUNTESS. Well?

THE RAGPICKER. Countcss, the world

has changed.

COUNTESS. Nonsense. How could it

change? People are the same, I hope.

THE RAGPICKER. No, Countcss. The

people are not the same. The people are

different. There’s been an invasion. An

infiltration. From another planet. The

world is not beautiful any more. It’s not

happy.

COUNTESS. Not happy? Is that true?

Why didn’t you tell me this before?

THE RAGPICKER. Bccausc you livc in a

dream, Countess. And we don’t like to

disturb you.

COUNTESS. But how could it have

happened ?

THE RAGPICKER. Countcss, there was

a time when you could walk around

Paris, and all the people you met were

just like yourself. A little cleaner, maybe,

or dirtier, perhaps, or angry, or smiling

— but you knew them. They were you.

Well, Countess, twenty years ago, one

day, on the street, I saw a face in the

crowd. A face, you might say, without a

face. The eyes — empty. The expression —

not human. Not a human face. It saw me

staring, and when it looked back at me

with its gelatine eyes, I shuddered.

Because I knew that to make room for this

THE MADWOMAN OF CHAILLOT 2^7

one, one of us must have left the earth. A

while after, 1 saw another. And another.

And since then, I’ve seen hundreds come

in — yes — thousands .

COUNTESS. Describe them to me.

THE RAGPICKER. You’ve Seen them

yourself. Countess. Their clothes don’t

wrinkle. Their hats don’t come off. When

they talk, they don’t look at you. They

don’t perspire.

COUNTESS. Have they wives? Have

they children?

THE RAGPICKER. They buy the models

out of shop windows, furs and all. They

animate them by a secret process. Then

they marry them. Naturally, they don’t

have children.

COUNTESS. What work do they do?

THE RAGPICKER. They don’t do any

work. Whenever they meet, they

whisper, and then they pass each other

thousand-franc notes. You see them

standing on the corner by the Stock Ex-

change. You see them at auctions — in the

back. They never raise a finger — they just

stand there. In theater lobbies, by the

box office — they never go inside. They

don’t do anything, but wherever you see

them, things are not the same. I remember

well the time when a cabbage could sell

itself just by being a cabbage. Nowadays

it’s no good being a cabbage — unless you

have an agent and pay him a commission.

Nothing is free any more to sell itself or

give itself away. These days. Countess,

every cabbage has its pimp.

COUNTESS. I can’t believe that.

THE RAGPICKER. Countess, little by

little, the pimps have taken over the

world. They don’t do anything, they don’t

make anything — they just stand there and

take their cut. It makes a difference.

Look at the shopkeepers. Do you ever

see one smiling at a customer any more?

Certainly not. Their smiles are strictly

for the pimps. The butcher has to smile

at the meat-pimp, the florist at the rose-

pimp, the grocer at the fresh-fruit-and-

vegetable pimp. It’s all organized down to

the slightest detail. A pimp for bird-seed.

A pimp for fishfood. That’s why the cost

of living keeps going up all the time. You

buy a glass of beer — it costs twice as

much as it used to. Why? lo percent for the glass-pimp, lo percent for the beer-pimp, 2o percent for the glass-of-beer-pimp — that’s where our money goes. Personally, I prefer the old-fashioned type. Some of those men at least were loved by the women they sold. But what feelings can a pimp arouse in a leg of lamb? Pardon my language, Irma.

COUNTESS. It’s all right. She doesn’t

understand it.

THE RAGPICKER. So now you know.

Countess, why the world is no longer

happy. We are the last of the free people

of the earth. You saw them looking us

over today. Tomorrow, the street-singer

will start paying the song-pimp, and the

garbage-pimp will be after me. I tell you,

Countess, we’re finished. It’s the end of

free enterprise in this world !

COUNTESS. Is this true, Roderick?

PIERRE. I’m afraid it’s true.

COUNTESS. Did you know about this,

Irma?

IRMA. All I know is the doorman says

that faith is dead.

DOORMAN. I’ve stopped taking bets

over the phone.

JUGGLER. The very air is different,

Countess. You can’t trust it any more.

If I throw my torches up too high, they

go out,

THE RAGPICKER. The sky-pimp puts

them out.

FLOWER GIRL. My flowcrs don’t last

overnight now. They wilt.

JUGGLER. Have you noticed, the

pigeons don’t fly any more?

THE RAGPICKER. They Can’t afford to.

They walk.

COUNTESS. They’re a lot of fools and

so are you! You should have told me at

once ! How can you bear to live in a world

where there is unhappiness? Where a

man is not his own master? Are you

cowards? All we have to do is to get rid

of these men.

PIERRE. How can we get rid of them?

They’re too strong.

(The Sergeant walks up again. J

COUNTESS (smiling J . The Sergeant will

help us.

SERGEANT. Who ? Me?

IRMA. There are a great many of them,

Countess. The Deaf-Mute knows them

2^8 JEAN GIRAUDOUX

all. They employed him once, years ago,

because he was deaf. (The Deaf -Mute

wigwags a short speech) They fired him

because he wasn’t blind. (Another Jiash of

sign language) They’re all connected like

the parts of a machine.

COUNTESS. So much the better. We

shall drive the whole machine into a

ditch.

SERGEANT. It’s not that easy, Countess.

You never catch these birds napping.

They change before your very eyes. I

remember when I was in the detectives . . .

You catch a president, pfft ! He turns into

a trustee. You catch him as trustee, and

pfft ! he’s not a trustee — ^he’s an honorary

vice-chairman. You catch a Senator dead

to rights : he becomes Minister of Justice.

You get after the Minister of Justice — he

is Chief of Police. And there you are — no

longer in the detectives.

PIERRE. He’s right, Countess. They

have all the power. And all the money.

And they’re greedy for more.

COUNTESS. They’re greedy? Ah, then,

my friends, they’re lost. If they’re greedy,

they’re stupid. If they’re greedy — don’t

worry, I know exactly what to do.

Roderick, by tonight you will be an

honest man. And, Juggler, your torches

will stay lit. And your beer will flow

freely again. Martial. And the world will

be saved. Let’s get to work.

THE RAGPICKER. What are you going

to do?

COUNTESS. Have you any kerosene in

the house, Irma?

IRMA. Yes. Would you like some?

COUNTESS. I want just a little. In a

dirty bottle. With a little mud. And some

mange-cure, if you have it. (To the Deaf-

Mute) Deaf-Mute ! Take a letter. (Irma

interprets in sign language. To the Singer)

Singer, go and find Madame Constance.

(Irma and the Waiter go into the cafe.)

SINGER. Yes, Countess.

COUNTESS. Ask her to be at my house

by two o’clock. I’ll be waiting for her in

the cellar. You may tell her we have to

discuss the future of humanity. That’s

sure to bring her.

SINGER. Yes, Countess.

COUNTESS. And ask her to bring Mademoiselle Gabrielle and Madame Josephine with her. Do you know how to get in to speak to Madame Constance? You ring twice, and then meow three times like a cat. Do you know how to meow?

SINGER. I’m better at barking.

COUNTESS . Better practice meowing on

the way. Incidentally, I think Madame

Constance knows all the verses of your

mazurka. Remind me to ask her.

SINGER. Yes, Countess.

(Exit.)

(Irma comes in. She is shaking the oily

concoction in a little perfume vial, which she

now hands the Countess.)

IRMA. Here you are, Countess.

COUNTESS. Thanks, Irma. (She assumes

a presidential manner) Deaf-Mute! Ready?

(Irma interprets in sign language. The Waiter

has brought out a portfolio of letter paper and

placed it on a table. The Deaf-Mute sits down

before it, and prepares to write.)

IRMA (speaking for the Deaf-Mute) . I’m

ready.

COUNTESS. My dear Mr. — What’s his

name?

(Irma wigwags the question to the Deaf-Mute,

who answers in the same manner. It is all done

so deftly that it is as if the Deaf-Mute were

actually speaking.)

IRMA. They are all called Mr. President.

COUNTESS. My dear Mr. President: I

have personally verified the existence of a

spontaneous outcrop of oil in the cellar of

Number 2 1 Rue de Chaillot, which is at

present occupied by a dignified person of

unstable mentality. (The Countess grins

knowingly) This explains why, fortunately

for us, the discovery has so long been kept

secret. If you should wish to verify the

existence of this outcrop for yourself, you

may call at the above address at three

p.m. today. I am herewith enclosing a

sample so that you may judge the quality

and consistency of the crude. Yours very

truly. Roderick, can you sign the

prospector’s name?

PIERRE. You wish me to?

COUNTESS. One forgery wipes out the

other.

(Pierre signs the letter. The Deaf-Mute types

the address on an envelope.)

IRMA. Who is to deliver this?

COUNTESS. The Doorman, of course.

On his bicycle. And as soon as you have

THE MADWOMAN OF CHAILLOT 2^9

delivered it, run over to the prospector’s

office. Leave word that the President

expects to see him at my house at three.

DOORMAN. Yes, Countess.

COUNTESS. I shall leave you now. I

have many pressing things to do. Among

others, I must press my red gown.

THE RAGPICKER. But this Only takes

care of two of them, Countess.

COUNTESS. Didn’t the Deaf-Mute say

they are all connected like the works of a

machine ?

IRMA. Yes.

COUNTESS. Then, if one comes, the

rest will follow. And we shall have them

all. My boa, please.

DOORMAN. The one that’s stolen.

Countess ?

COUNTESS. Naturally. The one the

prospector stole.

DOORMAN. It hasn’t turned up yet.

Countess. But someone has left an ermine

collar.

COUNTESS. Real ermine?

DOORMAN. Looks like it.

COUNTESS. Ermine and iris were made for each other. Let me see it.

DOORMAN. Yes, Countess. (Exit Doorman)

COUNTESS. Roderick, you shall escort me. You still look pale. I have some old Chartreuse at home. I always take a glass each year. Last year I forgot. You shall have it.

PIERRE. If there is anything I can do. Countess . . . ?

COUNTESS. There is a great deal you

can do. There are all the things that need

to be done in a room that no man has

been in for twenty years. You can untwist

the cord on the blind and let in a little

sunshine for a change. You can take the

mirror off the wardrobe door, and deliver

me once and for all from the old harpy

that lives in the mirror. You can let the

mouse out of the trap. I’m tired of feeding

it. (To her friends) Each man to his post.

See you later, my friends. (The Doorman

puts the ermine collar around her shoulders)

Thank you, my boy. It’s rabbit. (One

o’clock strikes) Your arm, Valentine.

PIERRE. Valentine?

COUNTESS. It’s just struck one. At one,

all men become Valentine.

PIERRE (he offers his arm). Permit me.

COUNTESS. Or Valentino. It’s obvi-

ously far from the same, isn’t it, Irma?

But they have that much choice.

(She sweeps out majestically with Pierre. The

others disperse. All but Irma.)

IRMA (clearing off the table). I hate

ugliness. I love beauty. I hate meanness.

I adore kindness. It may not seem so grand

to some to be a waitress in Paris. I love it.